Here you see me as a crafter, making all sort of stuff with my husband. I’m also a developer for a living, a job I love.

But I’m also an archaeologist. Yes, an archaeologist that now codes. Long story.

I used to work on digs and in museums, and even if now I have another job, I like to come back to my professional origins when I have the occasion. And I like that my archaeology passion has remained, next to my coding passion.

Reenactment, indeed, is for me the main way to keep my connection with my ever lasting love for ancient history. You reconstruct the past with digs, researches on finds, studying ancient texts, but also with the experimental part that reenactment can provide.

I’ve talked about how my husband made me my first lucet and how to weave easily with it. Now, I’d like to guide you in a journey to discover more about the history of this ancient tool.

Here you’ll find a brief recount of my researches and all my resources.

And if I sparked your curiosity, I also wrote a book about the lucet: The Lucet Compendium. A historical exploration and practical guide.

Table of contents

What is a lucet?

Rici using a lucet during a reenactment

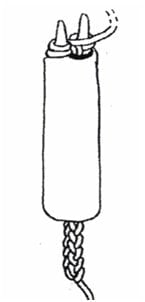

The lucet is a tool for cordmaking or braiding. Cords, shoelaces, drawstrings, laces for hair or clothing fastening were made by hand, before the industrial revolution, and some say that the two-pronged item known as lucet was one of the making methods.

Nowadays, hand-making cords is not common: with the creation of machines to make leaces quickly and cheaply, hand tools for the same purpose disappeared. You can see it used during historical reenactments, though, mainly Medieval-themed events. There, you’ll see lyre-shaped wooden lucets, with two prongs to weave the cord, sometimes a hole to host the cord during the process, sometimes with a handle.

Well, the debate about the ancient shape of lucets and the use of tools catalogued as cordmaking instruments starts here. Are those lucets we see in Medieval fairs a historically accurate item?

The cords made with such a tool are square, strong and slightly elastic, useful for hanging tools from a belt or as clothes accessories and decorations.

The making process is easy and quick to learn, after a short practice you can do it without thinking. You don’t need to pre-cut your thread to a specific lenght, and this is super handy, so you can make a cord of any lenght even without deciding the size first.

Also, the use is open to several techniques and variations to obtain braids with different colors and styles.

How to use a lucet fork?

I often use the lucet to make braids and cords for reenactment projects, but it could be super useful even in everyday life. The basic tecnnique is super easy! Follow a step-by-step tutorial, with photos and video.

Archaeological finds through the Middle ages

The question of the lucet: the origins and the shape

Several techniques for making braids with fingers or tools have been around for thousands of years, and are still in use today.

What about the original tools that have been used for millennia?

The problem with identifying an ancient lucet in an archaeological dig is that this tool is no more complicated than using any branch with two twigs or part of a horn with two prongs or other two-pronged items to braid cords. All the items I present in this article might be lucets, are considered lucets, but no definitive proof has been found yet.

You’ll find what literature says nowadays, what my opinion is and why. My research is still going on, as you’ll read in the conclusions. Nonetheless, I hope I was able to clarify most aspects about the finds associated to lucetting I was able to discover.

First of all: findings. Do we have evidence of tools used as lucets in ancient times? When are they dated? There’s not universal agreement among experts: everything about the so-called lucet is controversial, from the shape to its origins.

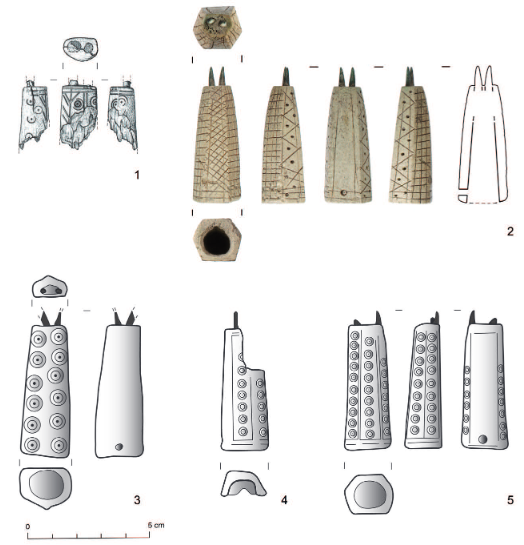

Archaeologists say we have a short number of finds through the Middle Ages that could be called lucets, but they’re easily misunderstood, in one way or another. Those first so-called lucets were simple, made from readily available material such as bones. They’re in most cases hollow bones with two prongs on top, sometimes with also a third larger prong of uncertain use. They are usually considered by the excavators to be disposable tools.

We don’t know how many items the archaeologists simply catalogued as bone findings, not recognising they had a purpose. If not decorated and maybe broken, the misunderstanding is an easy one. It can happen, for example, for bone whistles: if you don’t notice the aligned holes because your find is broken, you can easily label it as meal remains.

Confirming that a tool is a lucet used for cordmaking is very hard also because the context is not always enough of a help. Moreover, there’s not a specific shape that’s universally recognised as a lucet: there’s a variety of two-pronged objects (even three-pronged!) that have been identified as tools for cordmaking, flat or hollow tubes.

The York finds in bone and in antler

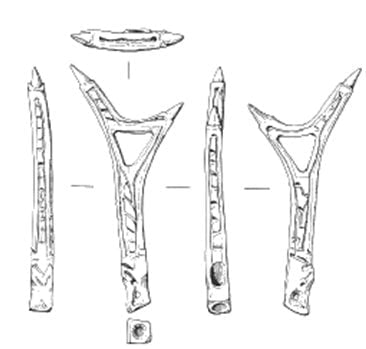

There are finds from Lund (Sweden) or York (UK) that among the most famous items that were catalogued as lucets, distinguished thanks to their carved decorations. The Lund item is a hollow bone, while the York finds are of two types, the antler ones are more similar to the lyre-shape that’s common from the 18th century, the bone ones are a sort of half-way between the hollow bone type and the flat modern type.

The York antler lucets, in my personal opinion, are quite controversial. I didn’t find other evidences of antler lucets, moreover their shape is not so comfortable for lucetting: the two prongs are too distant and diverge from each other, weaving with it would not be easy, I think. They are sometimes catalogued as pendants, because they have signs of wearing around their hole that are compatible with suspension.

The bone finds from Coppergate, on the other hand, have more similarities to the other ones catalogued as lucets.

They are made of bone, as the most part of presumed Medieval lucets are, and the two prongs are parallel, as we can see in more common findigs from Scandinavia. They are trimmed cattle nasal bones, bearing few signs of modifications and without any sign of wear around the two parallel prongs.

For many, the lack of such signs is a proof against the use of those artifacts for braiding. They are so rough that they could easily be butchery leftovers that were mistaken for tools.

As it’s often noted, any two-pronged item could serve as a lucet, and that’s one of the most significant drawbacks for any research about the medieval history of such a tool.

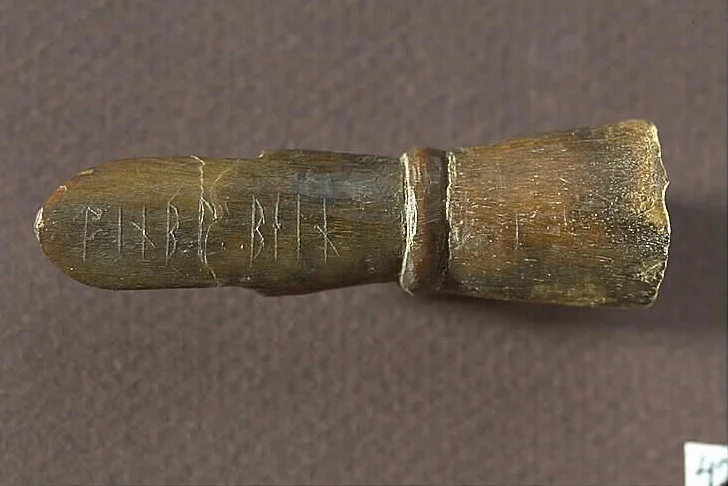

The artifact from Lund has also an inscription in runes: the recent studies of the inscription gave a boost to its identification with a cordmaking utensil, and even gave the name for similar tools in the Scandinavian area. It’s from this find that the tools with similar hollow shape have been catalogues as lucets and referred to as tinblbein.

That’s maybe the most important find of its kind to-date, so it’s worth a specific insight.

The tool from Lund and its inscription: the forefather of all Medieval lucets

The Lund artifact is small piece of tubular sheep bone 65mm long and with a diameter of 20mm. It has finely carved teeth, two shorter and thinner ones aligned with each other, plus a larger one behind. It’s contextually dated to the second half of the 11th century.

It’s famous for its two-word runic inscription.

Here’s the abstract from the research published in 2021 on Danske Studier:

The artefact is contextually dated to the second half of the 11th century. The bone piece is provided with finely carved teeth and carries an inscription in runes. The identification of each rune character is uncomplicated. The inscription says: tinbl:bein.

The second sequence bein represents the noun Rune Danish bæin, Old Danish bēn ‘bone’ in all probability with reference to the piece itself and it is plausible that the inscription forms a compound designating the utensil in question, but which utensil? The difficult task is to interpret tinbl? The first suggestion by the late runologist, Erik Moltke, related the runes to the noun Rune Danish tæinn, Old Danish tēn ‘spindle’ and alternatively, to the noun and verb Old Danish twinnæ ‘a twine/to twine’ suggesting the artefact being a utensil for twining threads together, i.e. a twining-bone. Erik Moltkes suggestions seem neither linguistically nor technically convincing. The bone piece was a unique find in 1961, but now a number of similar archaeological artefacts seem to constitute a whole group. In this article, I suggest that the sequence tinbl reflects the noun Old English timple known as a loan word in post-medieval Nordic languages. The present day English form is temple and the present day Danish form is tempel and the word designates an implement used in weaving. Consequently, the runic object must be a temple-bone (Old Danish *timpelbēn) an end-piece of a primitive medieval temple.

The first part of the inscription is the most interesting one for us here. Tinbl is considered by Olesen the modern form temple, that designs a weaving tool to maintain the warp width and prevent narrowing. Consequently, the inscription designates the object as a “temple-bone” (Old Danish *timpelbēn).

Those two words give us a precious context for the use of the tool bearing them in relation to textile production. From here, the archaeologists started referring to any artifact with a similar shape to the Lund find.

The identification with the end-piece of a temple is tricky, though: you need two Lund-like items to make a temple, but in most cases those finds are unique. So, someone proposed that solitary artifacts could have another function, original or repurposed, as lucets. Experimental archaeology supports this theory, as we’ll see. In 1968 Kerstin Petterson reproduced with a hollow teethed tool two extant braids from a woman’s burial in Gotland (Sweden). More recent tests with artifacts from Sigtuna (Sweden), Oslo (Norway), Douai (France), Tyrol (Austria), all dated between the 10th and 13th century, gave the same results. All showed the most significant problems were the shortness of the tool and the thin space between the prongs, but lucetting produced a cord quite easily, nonetheless. So the use of those artifacts as lucets seems possible.

Nowadays, following those studies, the word tinblbein has become a synonym for lucet.

The hypothesis of the weaving temple

The hypothesis of the weaving temple has sparked differing opinions among scholars, with some finding it convincing while others see it as problematic.

The widely accepted function of a temple is to maintain the width of the weaving, ensuring it remains uniform throughout the process and preventing it from narrowing. Modern temples, typically made of wood or metal, are adjustable in length and feature small nails at one end to secure the fabric’s edges.

While the Lund artifact resembles an end-piece of such a tool, it’s essential to note that a complete temple would require two such pieces, one for each side of the fabric. However, most discoveries like the Lund artifact are singular, raising questions about their intended use in such a weaving context. Although some finds have been unearthed alongside weaving-related items like loom weights, direct associations with weaving techniques remain scarce.

Moreover, preserved medieval temples typically feature more prongs than the Lund artifact, casting doubt on its role as a temple.

Another factor to consider is the hollow nature of the Lund item. For it to function as a temple mounted on a stick, a hollow end-piece would be expected, but it would ideally be closed on one end or have its body narrowing towards the tips, to accommodate the stick securely. While in most of the similar artifacts the body of the tool narrows towards the top, it’s not always the case.

Given the intricacies surrounding the temple theory, many researchers have proposed alternative functions for solitary artifacts like the Lund find, suggesting they may have been repurposed or served multiple original functions. Considering the significant investment of time and resources required to produce such artifacts in ancient times, it’s unlikely they were crafted without practical purpose. Both the temple and lucet functions are inherently linked to textile work, adding weight to the idea of multifunctional artifacts.

Experimental archaeology further supports the notion, particularly with the pioneering tests conducted by Kerstin Petterson in 1968.

A glimpse on interesting finds

The artifacts that have been identified as lucets are just a few and scattered throughout Europe, with a concentration in Sweden and Scandinavia in general. Most of them date back to the period between 10th and 13th century.

The fact that they are such a small number is more of a problem for their study, since any kind of statistics become tricky. The latest years gave a boost to research on the matter, though, so my list remains a work-in-progress, as the studies sum up.

Sweden

The greatest number of lucet finds to date comes from Sweden. It could be because the Lund find is Swedish, or because local archaeologists are more sensitive on the lucet question, or just by chance.

In particular, the city of Sigtuna has given hundreds of those bone artifacts, now preserved in the Sigtuna Museum: if you visit its online archive and search for “tinblbein“, you find 85 items. The museum experts consider them to be common everyday tools, judging from their number.

The Sigtuna finds are less than 70mm long, some of them even smaller, a few with carved decorations. They all date from the 10th -12th century. They were found in association with Medieval textile crafts, along with finds of loom parts, metal sewing needles and bone needles for needlebinding. It’s not usual, I know just of a case in France where those artifacts were found in such a context.

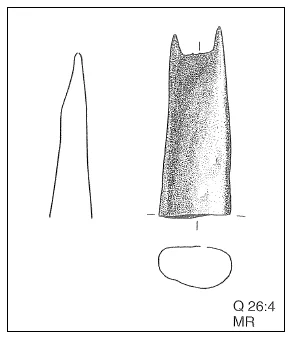

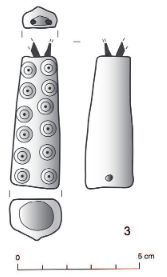

A remarkable find is the bronze tool from Hossmo (Sweden), coming from a 2003 dig just outside the town cemetery. At first identified as a spinner, it was then compared to a similar find from Eketorp III, the medieval fortification of Öland (Sweden), so catalogued as a twining bone or tinbl bein, as artifacts with such a shape are called from the most famous find of Lund.

Another similar bronze tool was found in Övra Vannborga in connection with investigations of the years 1989-1991 in a context dated circa 600-800. This find is pretty ancient compared to the other possible lucets I mentioned.

And I discovered those are not the only metal tools that could be catalogues as lucets. From a survey in a manor house in Borg (Sweden) in 1992-93 emerged an iron tool, contextually dated to the Middle ages that could be compared to the others I listed.

It still seems that tools which could be identified as lucets are rare in metal. Since metals are non-perishable materials, if those tools were common in iron or bronze, we should have found more of them. It’s likely that instruments for such a household use were made of less noble and expensive material. More than one archaeologist underlined how lucets were probably disposable tools, as easy to make as to discard after use. We also have to consider that metals were often reused to make other things, though: this may be another reason for not having more finds like those.

My question here, though, would be: if you need a tool for a task and make yourself one, why you should make, use and discard? Ancient civilisations, for what I know, didn’t have the same frequency with disposable tools that we have nowadays. Wouldn’t be better to make a tool, as easy and quick and cost-labor effective as it may be, but one that you could reuse as you needed? A still open question, here, I suppose.

I also found that in 2010 in the excavations of the Örja village, just outside Landskrona in Sweden, the archaeologists found two quite interesting tools. They digged a large Iron age settlement with four farmsteads used through the Roman era until the Middle Ages and also a Stone Age (ancient Neolithic) dolmen.

From the yard number 12, they dug out two items with a strong resemblance to the Lund lucet. The archaeologists even called them “of the tinbl bein type” (“av typen tinbl bein”) mentioning the inscription on the Lund find.

Paul Eklöv Pettersson, antiquarian at the Historiska Museet, Lund University, said that those items have both been found in yard number 12 in connection with house number 11, which is dated too the 13th century.

The two Örja finds are about the same size (about 6 cm). They are made of a smaller tubular bone, where the ends have been cut off and dug out of the marrow. Both tools have at one end two cut-out horns and a slightly wider prong, while the base is cut straight.

Between them, the tools are quite different. One has a very slender shape and is richly decorated on all sides with different types of angled lines. On this object, the two horns are slightly lower in relation to the wide prong. The other one is of a slightly simpler kind and doesn’t show the same craftsmanship of the first.

Also the lucet from Lund has two smaller prongs and a wider one. Since the later lucets have just two prongs, this shape seemed quite strange, to me, when I first saw it, to be associated to lucets. The Örja archeaologists seem so sure about the purpose of those two tools, because studies have shown confidence in defining the Lund find as a tool for cordmaking. I’m still curious about the purpose of the third bigger prong: what could have been its use, I have no clues.

Another unique find comes from Linköping (Sweden), Brevduvan neighborhood, because of its features and its later date.

This tool has three holes, like a flute, but two prongs, like a lucet. The researchers thought the tool was born as a flute but, when it became useless as a musical instrument, it was repurposed as a lucet.

The find was linked to phase 5, which dates from the end of the 14th century to the second half of the 15th century, quite late compared to the other Swedish lucets.

France

Another group of finds I think interesting are three bone tools from the abbey of Wandignies-Hamage (France), from the excavations conducted in 1991-2002 and now preserved in the Arkéos Musée in Douai (France). They are catalogued as “tricotins” and dated to the 10th century. They are associated with other textile implements, thus giving us a clue for their use in textile working.

In my opinion they have a very strong resemblance to two decorated items from Sigtuna (Sweden), about which you can read later on.

I’m trying to discover more about those tools and their context: the association with other pieces used in textile work seems quite interesting to me.

About dates, all the above mentioned finds come from the early Middle Ages (before the 13th century) from the British isles or Northern Europe. See the timeline for a global view on the datings.

Rare findings of braids

What about archaeological finds of braids? Textiles are rarely preserved because of their perishable nature, so examples of braids are quite rare.

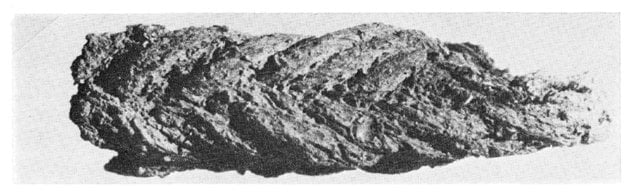

There could be evidence from a woman’s burial from Barshalder, Grötlingbo parish, Gotland (Sweden): it’s from the late 11th century and, among the rich textile finds, we have two braided cords. It seems that one of them had beads, and the other seemed to be fastened to a tortoise brooch, in a position that suggested it was used as a shoulder strap.

They are both square in section and roughly 3-4 mm and 1,5-2 mm across. The fact that they have a square section coincides with the outcome of a lucet braiding: indeed, Kerstin Pettersson wrote about this find in 1968 that experiments showed that a tool with two prongs gave a result close to the original cord.

Also, those cords seem made from a continuous length of string, like a lucet braid would. Cords made by fingerlooping, for example, are not made from a unique lenght of thread.

About the real use: a long-dated controversy

As for the use of all those Medieval finds for cordmaking, the question is still debated. If the tools are not found in a context that helps specify their purpose, any theory can be valid. Unfortunately, we don’t know yet of a two-pronged object that’s been found in connection with a braid as to prove their direct correlation.

Also, it’s been noted (p. 1790) that some of those lucet-like finds don’t carry any sign of wearing around the prongs to suggest their continual use for cordmaking. As I mentioned before, though, some of those tools, mainly the ones made in bone, could easily be disposable: this way, a short use time could be the reason for not having signs of the continual passing of thread.

I imagine, if this is true, that a sort of lucet was not needed on a daily basis: whenever a person needed one to make a cord, she could just pick a bone remained from a meal, cut-out two prongs, use the lucet and forget about it. I am still dubious about such a way of using a tool you need to make yourself for such a task as cordmaking.

There’s another fact. I spoke with a few luceteers who use their tools quite a lot, they all told me they don’t see significant signs of wearing, even after a constant use. I have to note that their most used lucets are the wooden ones. Rosalie Gilbert, though, told me the same about her bone lucet she’s been using constantly for 15 years. I’d like to do a test myself about it and come back with more proofs.

Experimental archaeology: tool from Barshalder (Sweden)

We know of a few attempts at experimental archaeology to find a solution to the question about how those tools were used in practice.

The first one was Kerstin Pettersson, who wrote in 1968 about the two braids found in Gotland, Sweden. With a reproduction of the bone artifacts from Lund or Sigtuna, she tried to make a cord to reproduce the ones found in the woman’s burial from Barshalder. Well, to definitely prove how the original braids were made, she should have unweaven them (thus meaning, destroy them!) to see if they were made with just one single thread. Even though nobody wanted to do that, Petterson concluded it was highly likely that the braids from the grave were made with such a tool. The braid is fed downwards through the hollow bone as we do through the hole in modern lucets, while it’s produced on the prongs.

Pettersson tried several braiding techniques before lucetting, but none of them produced cords like the ones from Barshalder. She then tried different kinds of tools, with two, three or four prongs. The cords made with three and four-pointed tools came out too thick, the ones made with a two-pronged instrument were instead identical to the ones she studied, at least on the surface, without “un-braiding” the originals for a deeper look.

Still, there’s someone debating that this test or any other after that were unconclusive.

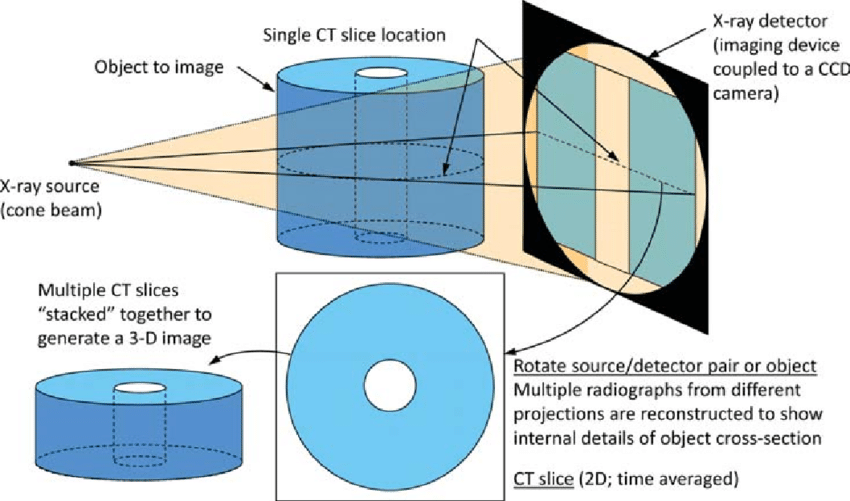

And, actually, my engineer husband pointed out that unravelling an ancient cord would not be the only way to ascertain how it’s made on the inside. We live in the 21st century and have access to technologically advanced nondesctructive analyses that in the 1960s were not common or even not yet available for archaeological studies.

X-Ray Computed Tomography is the technique he would suggest. It’s used, mainly in medical applications, to create a 3D model of the internal features of a solid object without destroying it.

Such a technique would be really useful in the study of the braids from Gotland: it could give a glimpse on the technique used to make them.

Experimental archaeology: a find from Norway

A recent find from Norway, from the Follo Line project in Oslo in 2017, gave the opportunity to the archaeologist Sara Langvik Berge for another experimental cordmaking.

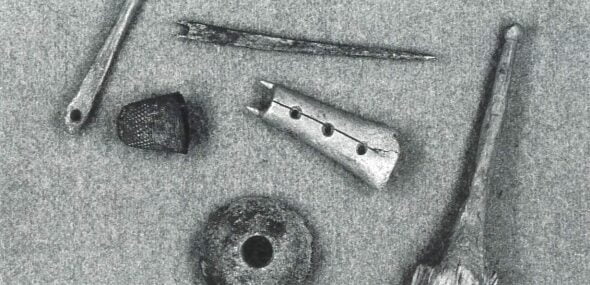

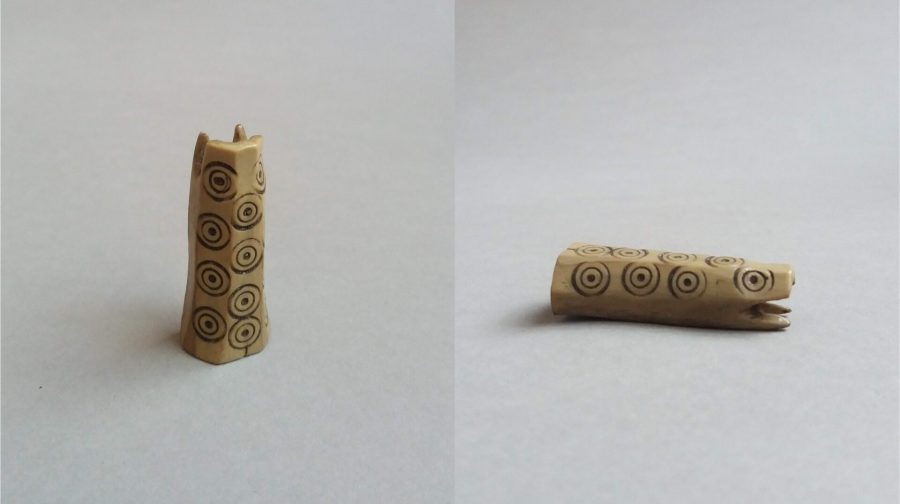

The find is a small object made of polished bone or antler, 3.6 cm long, hollow and adorned with typical medieval dot circle decor. At one end it has two small tips and dates back to the Middle Ages. The NIKU archaeologists said it was found in a huge refuse layer or landfill area that had to be removed by machine under time pressure, but they would date it to the 13th century, based on finds from the same context.

At the beginning, its purpose was unclear, but when in December 2017 the archaeologists published its photo on their Instagram profile, a Swedish follower commented “Ett tinbl-bein!” (“It’s a tinbl-bein”), referring to the Lund tool and its runic inscription.

After the attempt to make a string with the Norwegian tool, the archeaologists suggested that originally they must have had a small hook or similar to lift the lower thread over the prong. That would have been helpful, with such a small tool, but they said that if you hadn’t fingers too big you could use it nonetheless. Moreover, the use of a hook or crochet to help with lucetting is documented also in modern times.

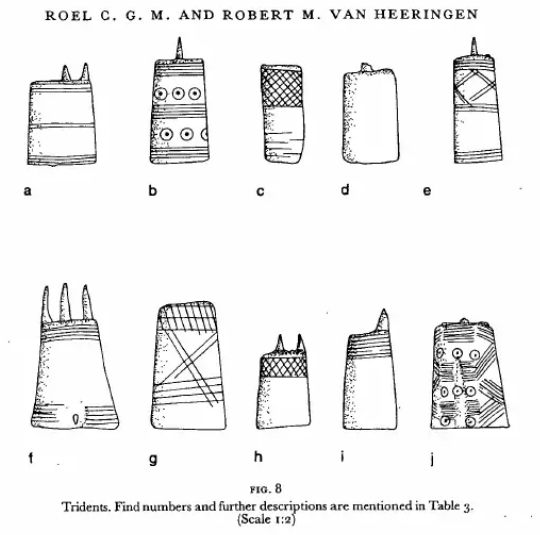

Comparison with the tridents from The Netherlands

About the possible use of those hollow bones as lucets, I found an interesting point of view regarding a few 10th century tools from the circular fortress of Oost Souburg in the Netherlands.

The researchers here study a few decorated tools made from hollow bones. Nine of the ten finds are decorated. The objects were made selecting and working bones to obtain a rounded front and an almost flat back, which is always undecorated. The tools have three sharp and short teeth, maybe for pricking rows of holes in leather, in their interpretation. They are polished also between the teeth, though, something that wasn’t needed for that use. The researchers suggest that such a polishing would suit best a sort of comb.

It’s noted that those bones are hollow by nature, but have been hollowed further, and have been worked to make the opening larger or smoother. While I could like the idea of them being lucets (and the larger number ever found together in the same context), it must be noted that the bone at the edge of the hole has not been polished. Maybe they are not lucets, even though the researchers note that the inhabitants of Oost Souburg were partly dependent on wool production, so it’s probable that those tools, considering their context, are related to wool working.

The fact that they have three teeth is another clue against their identification with lucets: even if you consider three prongs to be a good number for a braiding instrument (which I don’t) the three-pronged tools that are considered lucets by researchers have two equal prongs plus a bigger one, not three equal ones. Still, the purpose of the third bigger prong remains a mystery to me, it seems more of an obstacle while making a cord on the other two progs.

It must be noted that the absence of one teeth in those Netherlands tridents did not make the tool useless: the missing teeth was polished in some cases, so the tool must have served a purpose even with two teeth. Maybe some of them in some specific cases have been used as cordmaking tools, after all? We’ll never know that, unfortunately.

I would like to study them more, though, because I think they could help giving light on the other bone tools that are considered lucets. For the moment, I’ll not list them among lucets, personally.

The question of the size

About practicality, there’s also the problem of size. A few of the mentioned tools are quite small: the Norwegian find for example is just 3.6cm long, with very short prongs. As I said, the archaeologists trying to use it had a hard time at the beginning and suggested that the use of a small hook to lift the thread would make the use of the instrument easier.

The Sigtuna finds are less than 7cm, some of them very small. What is remarkable about those is their number: the museum states they have a hundred of them, all from the 10th-12th century.

I found a discussion in an interesting forum about those tools and their use. There, Ny Björn Gustafsson from The Archaeological Research Laboratory of Stockholm University said they are worn or polished on the prongs (maybe the signs of wearing some researchers look for?).

About their use to make cords, some argue that the prongs are too short, the thread would slip out quite easily. But others say (after a few tries with replicas) that, despite the tendency of thread slipping away, instruments like the Sigtuna ones can indeed be used as lucets, with a little care. The lyre-shaped modern version would probably be an improvement to prevent thread slipping. I personally tend to weave on my modern-shaped lucet very close to the end of the prongs, so maybe a shorter one would not be uncomfortable to weave on. The only problem could be holding it firmly because of the small handling space.

Ny Björn Gustafsson also tried using one of the tools from Sigtuna to make a cord, and it came out pretty well, despite how tiny they are. All the experimental archaeology tests I heard of concluded that lucetting with such artifacts is indeed possible.

About the other finds I mentioned, they are quite similar in size, and small. Just to mention a few:

- the inscripted Lund find is about 6.5cm long

- the Övra Vannborga metal tool is about 4cm long

- the Borg metal tool is about 8cm long

- the Hossmo metal tool is about 3.5cm long

- the finds from Örja are about 6cm long

Was there a reason to make such a small instrument, while a bigger one would certainly be more handy? I never tried lucetting with a 3cm pronged hollow tube, but now I’m considering to give it a try. I’d like to have a better hand myself on this problem.

I recently happened to try lucetting with a tiny wooden lucet, with straight prongs just 3cm long and 1.5cm apart. I found it quick to work with and comfortable to hold, but it had a handle almost 10cm long. So, my own test can’t be considered experimental archaeology like the others I mentioned, because the size and shape of my tool are different from any Medieval find.

Since those considerations I’m writing now are already dense, I’ll leave the question for another time and another post.

About size, there’s also the opposite problem: I saw someone considering a lucet also very big U-shaped tools, about 20cm long.

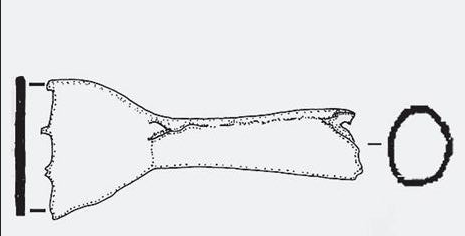

A few sites in Norway have produced those long “U-shaped objects made of whalebone. The most famous one (at least among people who studied the lucet question) comes from Sømhovd (Norway). It’s 22.1 cm long, 2.7 cm thick and 6.4 cm wide, now at the NTNU Vitenskapsmuseet (item n. T13471). It’s date is also not coherent with the Medieval lucets we considered here, since this whalebone tool comes from the Late Iron Age.

This item has been identified with a lucet, mainly by reenactors, due to its two-pronged shape, but its size and conformation makes it impractical for cord making. Consider that the size of the tool doesn’t matter in relation to the final cord size: any sized lucet would produce a similar cord with the same yarn, it’s just the yarn size that matters. In my personal opinion a lucet too big could be even less handy than the very tiny tools discussed above.

This Norway find has very thick prongs with a square cross section, so not exactly comfortable to lucet with. Maybe a very big lucet could be handy with really thick yarn to make big braids that could in some use cases benefit from the elasticness given by the lucetting technique, but I would expect prongs with a circular cross section.

Its original identification with a line winder, a fishing instrument used to wind fishing line, is most likely true, especially considering it’s comparable to some modern fishing tools.

Possible lucets from Tyrol (Austria)

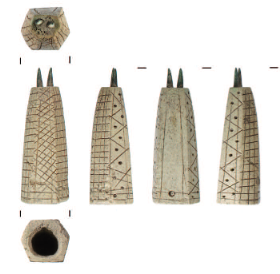

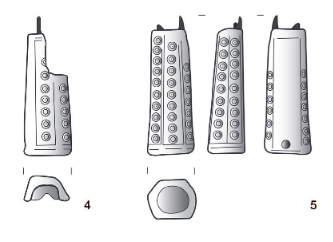

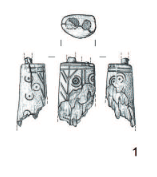

A research published in 2022 on “Strands”, annual journal of The Braids Society, gives a highlight on finds from Tyrol (Austria) that could be considered lucets. The author, Beatrix Nutz, shows five tools that are made of bone or horn and have two metal prongs each. Those tools were cautiously classified by the excavating archaeologists as “perhaps a device for making cords”: they were considered more like knitting spools or knitting Nancies, that are sometimes said to be connected to lucets.

The archaeological contexts go from the Late Antiquity to the 14th century, but in those cases the dates can’t be totally sure. The latest find of those five ones mentioned in the article was a stray find in 2018 by Christoph Hussl on a field west of the small town of Patsch, near Innsbruck in North Tyrol. Beatrix Nutx had the possibility to study this find, so it’s the first tool of its kind to be studied by an archaeologist specialising in textiles. She noted similarities in shape, material and size with other finds from Northern Europe said to be lucets, mainly the ones from Sigtuna.

The greatest difference is the presence of the metal prongs in the Tyrol tools, unseen to date in comparable Northern Europe artifacts. Another difference regards the body of the tool: while all the other bone findings we have seen have a hollow body that can be used to feed the cord inside, the Tyrol artifacts aren’t hollow. Those are only hollow at the bottom, and not between the prongs: the worked cord must be threaded through a small 2.2mm hole at the bottom of the undecorated side of the implement, from which it then passes through the hollow portion of the body and comes out. Another unicum of this tool is its hexagonal cross-section.

Beatrix Nutz was able to do some experimental archaeology with replicas. She used red silk thread for one experiment and two different blue wool yarns for other two tests. The experiments showed that lucetting with this tool is possible. Thin threads result in narrow cords that can pass through the bottom hole. To pick the stitches and pass them over the prongs you need the help of a needle or hook, as in the Norwegian experiments.

The author noted that the greatest problems are the short length of the tool (57 mm) and the short distance (a mere 5 mm) between the tips of the prongs. It’s strange to note that the tool is indeed large in proportion, being larger at the bottom (from 9mm to 21mm). I don’t know if it would be comfortable to handle, being so large in respect to its height.

There comes back my personal doubt: if you need to make a tool to perform a task in a more efficient way, why do you choose to make one so tiny? What’s the advantage, compared to bigger lucets or other braiding techniques? My question still remains open.

Thanks to Beatrix Nutz article I also discovered another interesting find from Netherlands.

This came from a dig in 1942 from Middelburg, Zeeland in The Netherlands and is dated 950-1050. It reminds me closely of the most famous of the Sigtuna lucets, the carved one.

Also this one is a two-toothed tool made of hollow bone (the museum website states from an animal leg, not telling which animal) with a high-gloss surface and with incised line decoration. Like the Sigtuna finds and other comparable ones, it’s tiny: 4.3 x 2.2 x 1.7 cm.

Those two prongs seem quite worn, one possibly broken. Could they have been longer in origin? The lenght of the prongs would not be the greatest problem, but the overall size would matter, mainly the distance between them. Tools like this are not easy to handle, the width of the prongs and their being so close would for certain mean that you need a hook to work the stitches. The more I see tools in this size and shape, the more dubious I am about their practical use as lucets.

New artifacts identified in Southern Europe

The research conducted by Beatrix Nutz is giving a real boost to the question of the lucet in Southern Europe. After the aforementioned finds from Tyrol (Austria), she’s currently studying more extant finds from Switzerland, Germany, Italy. I can’t wait for her new paper to be published! I had the priviledge of speaking with her about her research, but I’ll wait until the official publication, so I can give her proper credit.

In the meantime, I can cite an artifact from Italy, whose photos are available online.

From an early-Medieval layer of a settlement in Grado (Friuli Venezia Giulia, Italy) comes a tool about 50 mm long, with a flat back that has a small hole at the bottom. The front is decorated with two series of horizontal lines and diagonal ones crossing each other. It was found during the excavations conducted by the “Soprintendenza Archeologia, belle arti e paesaggio del Friuli Venezia Giulia”.

I got in touch with Dario Gaddi, who was part of the equipe of excavators. He said this Italian tool reminds him of the French finds from Hamage, mainly the one with horizontal lines on the front, even if the back of the French tool is not flat. He also suggested a connection with the tridents from The Netherlands. Besides the ones I mentioned from Oost Souburg, there are others from the Flemish and Southern Netherland coast, for example from Antwerp from the 10th-16th century. The researchers relate those Antwerp items to textile production. Far from being lucets, as I already said, I think knowing more about those tools could give valuable insights into all those two-pronged artifacts that are considered lucets.

And after the Middle ages? Actually, the lucets we see in Medieval reenactments strongly resemble the post-Medieval ones. I found no evidence of the lucet from the later Medieval period until the 18th century. Somebody says that the tool was used in the Reinassance, but I’ve not been able to find a single item from that period.

We have a 19th century example made in boxwood from the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, that’s not currently on display. It has the same shape of modern lucets, two-pronged, flat, wooden, with a central hole but no handle.

The Colchester Collections have two ivory lucets without handle, with curved horns and a hole at the base. The bigger one is 10cm long, the smaller one 8cm long. About this last one, the museum website states that it came with two examples of braiding, but I unfortunately couldn’t find photos of them.

It’s also possible to find lucets from the Victorian age on sale. I’ve found one made of bone, with an old label describing its purpose as a tool to make chains or braids.

A few museums in Northern Europe have several lucets in their collections, dating to the 18th or 19th century. Several pieces come from unknown sources or were purchased out of context, so giving them a specific date is hard. Comparing them to other tools, you could generally say they were made from the 18th century onwards.

We can also find a few lucets that were made with a lathe, by turning. One from the National Museum of Finland is dated to the middle of the 19th century. Other two examples from the Hallands konstmuseum in Halmstad (Sweden) have no date, but could be comparable to the Finnish one.

A notable lucet is one from the Hallands konstmuseum, that has several pieces but one in particular has an unfinished cord.

Another piece I think unique is the lucet from Enköpings Museum (Sweden): the only one I found with such a handle decoration.

It was donated to the museum in 1931, so it must be older, but not so much, judging from its features. It seems to me that it was made more as a decoration itself rather than a practical tool. He handle is carved, cave and has a square section that must make it uncomfortable to handle: it seems more an ornament to put on display, a nice gift for a crafter, than a comfortable lucet to use.

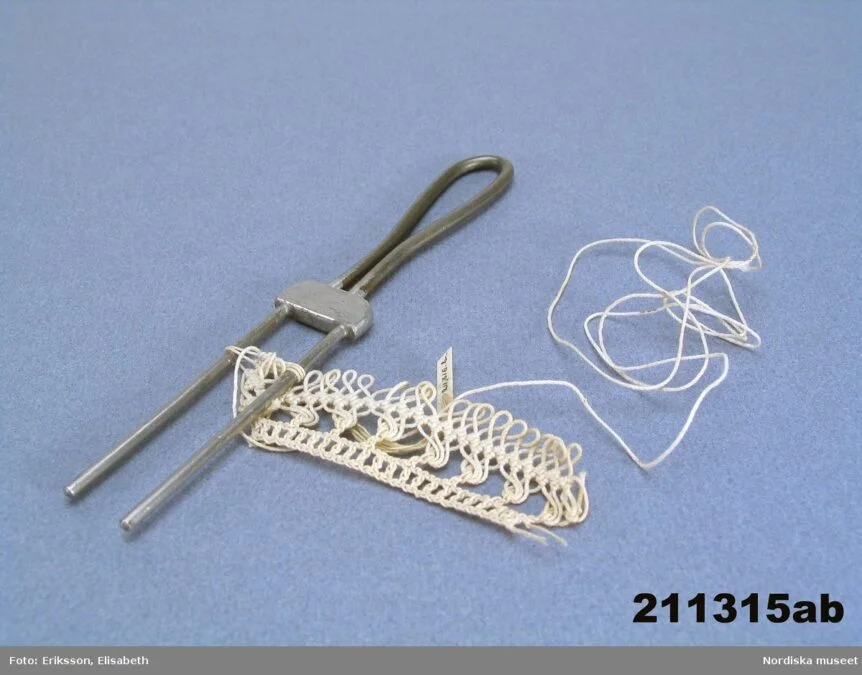

The Nordic Museum has another unusual lucet, an iron lucet with an unfinished cord. That’s not the usual one we can see, with a square section, but it resembles a crocheted piece. It doesn’t seem to me hairpin lace either, so the tool could be a lucet as the museum website states or a hairpin lace loom. Indeed, you could use the same tool for both crafts in many cases.

Among the post-Medieval lucets, the oldest one I came across is preserved at the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Donated to the museum by of Mrs. A. Dean Perry in 1967, it’s made of mother-of-pearl with gold decorations, without handle nor hole.The prongs bend slightly outward at the tips. It has incisions around the golden applique, both on the front and on the back.

It’s said to come from Vienna (Austria) from 1765 and it’s part of a sewing kit which items are made from the same material.

I think it’s the most exquisite and precious lucet I’ve ever seen. It’s part of a set whose items are all made of the same noble materials: a sewing box with extractable drawer, bobbins, a needle case, scissors, paper knives, pencil, thimble… Unfortunately, it’s not on display at the moment.

I think my search for lucets in museums could last forever! I’ve found several lucets (mainly after the 18th century) just browsing museum catalogues. As I came accross a museum with a lucet among its items, I discovered another, then more and more.

I decided to list all the items I could stumble upon. I’ll keep the list up-to-date as I find new ones. Please, if you happen to know finds I didn’t list, let me know in the comments!

Do you want to make your own lucet tool?

“If you can think it, you can make it”. Our #LRCrafts motto is here for a reason: when we need something, the first question is “can we make it?“. In most cases the answer is “yes”!

When I needed a lucet, my husband made a beautiful, handmade, functioning one just from a picture in half an hour. Find out how he made it.

Conclusions

The first lucet we made ourselves

Nowadays, when you see a lucet during a Medieval reenactment event, it’s usually lyre-shaped two-pronged and made of wood. It has a central hole just below the two prongs and can have a handle or not.

Looking at the few finds we have that are considered lucets, it seems that the most common shape during the Middle Ages, though, is of a bone tube with two prongs on one side, usually also a bigger third one. As you weave the braid, it goes inside the tube and comes out from the other opening.

If you live in a Medieval (or even Prehistoric household, I could venture) and need to make a two-pronged tool for braiding from the materials you have at hand, not needing a durable instrument, animal bones are convenient. Their shape provides a comfortable grip, they are readily available with no further effort after a meal, you can carve out two prongs and begin lucetting in no time. If the lucet breaks, you can just make a new one easily and quickly.

Also the antler lucets, like the one from the Yorkshire Museum, could be easy to make: the antlers provide two ready-to-use prongs, if you need a hole you can just cut it, but it’s not mandatory. Their shape is closer to the one we are accustomed to in modern times. Considering those specific York artifacts, I doubt they could be handy to use, though: the two prongs diverge too much and curve outwards, weaving the thread on them would be hard and uncomfortable in my opinion. I could agree with the experts who identified them with pendants, considering that they are decorated and that the evidence of wear around the holes could suggest they were was intended for suspension.

Well, the debate about ancient lucets is not settled yet.

Somebody states that none of the so-called lucets from archaeological sites has been unmistakably proven to be used for cordmaking. There are other techniques to make braids with a square section, other than using a two-pronged item.

Also, if the use of the lucet was common, even though with a disposable tool, somebody argued that there should be a single common shape. If it was a videly used tool, sooner or later the population using it would select a comfortable shape and use only that. We have to say that, even if we agreed on all those artifacts being lucets, we have few finds to give a useful statistic about the most common shape in a certain period and place. Our knowledge stops where the archaeological evidence stops, unfortunately, and we can’t consider the samples we have to be representatives to draw unmistakable conclusions.

I suppose the current distribution of artifacts (for what I know to date) reflects the sensitivity of researchers on the matter. In Viking areas of Northern Europe, maybe because of the recent studies on the Lund inscription, the possibility of the identification of a find with a lucet is more present to the excavators. Archaeologists are growing more and more aware of this possibility when they find tools with certain shapes. Going on in making a list of all the tools with the characteristics I dscribed here could be useful as a help in finding more evidences, being them pro or against the lucet theory.

Looking at the finds I was able to come to, I see that the so-called lucets have three macro-groups of shapes, the first two in use in the Medieval times (a variation of the same kind), the third one in the modern era:

- a hollow tube with two prongs at one end (with the Tyrol variation to be considered, where the tool is not hollow from end to end)

- a hollow tube with three prongs at one end, two smaller on one side and one bigger (I don’t consider the Dutch tools with three equal prongs)

- a flat two-pronged item, with or without a handle, with or without a hole

Loads of questions, now. Why three prongs? Maybe the bigger one was just a decoration of some sort, or it helped the weaving in a way we didn’t discover yet. Or it wasn’t a cordmaking instrument in the first place. Is there a relation between those objects and the bone tridents that came out of other archaeological sites, like the Dutch fortress of Oost-Souburg? Why, if those ancient tools are indeed lucets, after the Midle ages there was such a drastic change in the tool shape? Is that related to the lack of finds for a few centuries?

Another point came out while discussing with a reenactor. Compared to other braiding techniques, like fingerloop braiding, for which we have enough evidences, lucet is suited to make endlessly long cords. With fingerloop you need to pre-cut your thread, and even with long yarns you’d need more than one person to produce long braids, going beyond the length of one weaver’s leg. Would they need really long laces with the elasticity that lucetted ones can give during the Middle ages? I don’t have an answer for that. Yes, fingerlooping has a long tradition and is well tested. Somebody argues, why the need of lucetting, and of a specific tool besides your fingers?

Also, comparing fingerloop braiding to lucetting you see that the former is well documented also in images or written resources, while the latter is not.

So, the conclusions we can draw now are… unconclusive. Are all those finds lucets or something else? Both options could be true, considering the evidence we have at the moment. Also, some of the so-called lucets could be used for cordmaking, others not.

The problem is, in my opinion, that we could settle this debate forever only if we came accross an unmistakable evidence of such an artifact being a lucet. If we found a site with a tool that has the unfinished cord attached, for example, that would be definitive proof.

To disprove instead the existence and use of such lucets in a specific era, we should find a comparable item in another context of use. But if they are just broken bones that remained from a meal, or pendants, or decorative objects, or fishing tools, or whatever, we’d never know for sure, considering the actual contexts we have now.

So, we still have to research about the matter, and that’s what I love about archaeological research: it never really ends. Indeed, it’s for this reason that I got involved in studying the history of those tools that somebody called lucets. Be sure, my research doesn’t stop here! I hope to come back again soon with news.

Book "The Lucet Compendium"

“The Lucet Compendium. A historical exploration and practical guide” is the book by Sara Rossi and Daniel Phelps, published in The Compleat Anachronist series in 2024.

It showcases the archaeological researches conducted by Rici about the history of the lucet and different lucetting techniques developed by the author of “The Lucette Book“.

Resources

Lucets in museums

This list would like to be complete, but it’s not fully comprehensive of all the artifacts identified as lucets that are now preserved in museums. And for each museum I tried to list all the artifacts I could find: maybe some instititutions have other lucets I was not able to discover. I also listed extant finds under “Unknown museum“ where I could not find the actual institution preserving them.

Fow now I decided not to list recent items (post-18th century) coming from private collections of non-museum associations.

I’ll try to keep this list up-to-date and add all the artifacts I can find. If you know of any missing item, please tell me in the comments! Thank you!

Austria

- Unknown museum

- Stray find from a field near Patsch, North Tyrol (Austria), Middle ages

- Decorated carved bone tool from archaeological ruins in Kirchbichl, Lavant, East Tyrol,

(Austria), Late Antiquity – Early Middle Ages

- Stray find from a field near Patsch, North Tyrol (Austria), Middle ages

- Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum, Innsbruck (Austria)

- Possible bone lucet from Sonnenburg castle ruins, Natters, North Tyrol (Austria), 13th-14th century

Denmark

- Djurslands Museum, Grenå (Denmark)

- Two wooden lathed lucets, 1950s

- Museum Sønderjylland, (Denmark)

- Dark wood lucet, 1850-1920

- Carved wooden lucet with unusual shape, 1850-1920

- Wooden lucet with unusual handle, 20th century copy of a 19th century original

Finland

- Stundars Museum, Solf (Finland)

- Lucet with engraved date, 1865

- Kullaan Kotiseutu ja Museoyhdistys, Leineperi (Finland)

- Wooden lucet, undated but probably after the 18th century

- The National Museum of Finland, Helsinki (Finland)

- Lucet made by turning with a small knob of bone at the tip of the handle (classified also as a tool for hairpin crochet), middle 19th century

- KAMU Espoo City Museum, Espoo (Finland)

- Skirt with lucetted braid at the hem, 1860 – 1900

- Various Finnish museums

- Various Finnish wooden lucets, some undated, probably after the 18th century

France

- Arkéos Musée, Douai (France)

- Three “tricotins”, 10th century

Germany

- Hellweg Museum, Geseke (Germany)

- Two walnut lucets without handle, 1900-1975

Italy

- Unknown museum

- Bone lucet from Grado (Friuli-Venezia-Giulia, Italy), early Middle Ages

- Landesmuseum Schloss Tirol – Castel Tirolo, Dorf Tirol, Bolzano-Bozen (Italy)

- Fragment of an unidentifiable bone handle, pentagonal in cross-section with broken iron prongs, 12th century

Norway

- Museum in Nord-Østerdalen, Tynset (Norway)

- Wooden lucet, 1850 — 1940

- Two wooden lucets, one with unfinished cord, pre-1961 (year of acquisition)

- Sverresborg Trøndelag Folkemuseu, Trondheim (Norway)

- Lucet with hand-spun woolen yarn and unfinished cord, undated but probably after the 18th century

- Bone lathed lucet with twisted handle, undated but probably after the 18th century

- Domkirkeodden, Hamar (Norway)

- Wooden lucet, undated but probably after the 18th century

- Helgeland Museum (Norway)

- Wooden lucet, undated but probably after the 18th century

- Norsk Folkemuseum, Oslo (Norway)

- Lathed wooden lucet with a small hole at the conjunction of the prongs, pre-1941 (year of acquisition)

- Mahogany lucet, undated but probably after the 18th century, likely quite recent

- Tool classified as pointing stick, probably a lucet, with heart-shaped hole, undated but probably after the 18th century

- South Troms Museum (Norway)

- Wooden lucet, undated but probably after the 18th century

- De Heibergske Samlinger – Sogn Folkemuseum, Kaupanger (Norway)

- Pine wood lucet, engraved with M.H. 68, which means “Marie Heiberg 1868” (the donor), no photo available, 1868

- Unknown location

- Bone lucet from Oslo, Norway. Middle Ages

Sweden

- Unknown museum

- Flute repurposed as a lucet, Linköping, Brevduvan neighborhood, end of 14th – second half of 15th century

- Kulturen i Lund (Sweden)

- Sigtuna Museum (Sweden)

- Tempelben or carved lucet from Sigtuna, 1050-1075

- Lucet with dotted decoration, 1020-1050

- Several lucets from the Viking age, 10th – 12th century

- Lunds Universitets Historiska Museum (Sweden)

- Decorated lucet n.1 from Örja, 13th century

- Decorated lucet n.2 from Örja, 13th century

- Swedish History Museum Historiska, Stockholm (Sweden)

- Iron tool, maybe lucet, from Borg, Middle ages (1100-1500 ca)

- Kalmar Läns Museum (Sweden)

- Bronze lucet from Hossmo church dig of 2003 (Sweden), 7th-13th century

- Deer antler lucet with a hole at the base of the handle, incision VL or VJ (J-inverted), undated (used in Bläsinge, Norra Möckleby parish on Öland; purchased in 1908 by the Museum)

- Birch or beech lucet, undated (used in Glöminge, Glöminge parish on Öland; purchased in 1906 by the Museum)

- Wooden lucet with a knob at the tip of the handle, undated (used in Högsrum parish on Öland; purchased in 1903 by the Museum)

- Skellefteå Museum (Sweden)

- Lucet fork, undated but probably after the 18th century

- Torekällberget Open Air Museum, Södertälje (Sweden)

- Hallands konstmuseum, Halmstad (Sweden)

- Wooden lucet, undated but probably after the 18th century

- Lucet, undated but probably after the 18th century

- Two wooden lucets made by turning, undated but probably quite recent, as the mid-19th century lucet from the National Museum of Finland

- Wooden lucet, undated but probably after the 18th century

- Wooden lucet with an unfinished cord, undated but probably after the 18th century

- Wooden lucet with prongs uncurved at the tips, undated but probably after the 18th century

- Wooden lucet, undated but probably after the 18th century

- Enköpings Museum (Sweden)

- Lucet with carved handle, pre-1931 (year of acquisition)

- Lucet in turned wood, pre-1931 (year of acquisition)

- Sörmlands Museum, Nyköping (Sweden)

- Lucet from Sörbystugan in Bälinge parish, pre-1933 (year of acquisition)

- Regional Museum Skåne, Kristianstad (Sweden)

- Two dark wood lucets, undated but probably after the 18th century

- Lake Vänern Museum (Sweden)

- Wooden lucet made in one piece, 19th century

- Malmö Museum (Sweden)

- Beech lucet with heart-shaped hole and inscription “EID”, pre-1936 (year of acquisition)

- Bi-colored lathed lucet made of wood and ivory, 19th century

- Bone lucet with a small knob at the tip of the handle, 19th century

- Wooden lucet, pre-1911 (year of acquisition)

- Mahogany lucet with curved prongs, 19th century

- Wooden lathed lucet with bone-shod holes, 19th century

- Upplands Museet, Uppsala (Sweden)

- Wooden lucet, pre-1970 (year of acquisition)

- Nordiska Museet, Stockholm (Sweden)

- Iron lucet or loom for hairpin lace, pre-1937 (year of acquisition)

- Wooden lucet made by lathe, undated but probably after the 18th century

- Örebro County Museum (Sweden)

- Wooden lucet with signs of wearing on the prongs, undated but probably after the 18th century

- County Museum Gävleborg, Gävle (Sweden)

- Wooden lucet with bicolored unfinished cord, pre-1944 (year of acquisition)

- Österlens museum, Simrishamn (Sweden)

- Wooden lucet, undated but probably after the 18th century

- Gothenburg City Museum (Sweden)

- Wooden lucet, pre-1919 (year of acquisition)

The Netherlands

- Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden (Netherlands)

- Possible lucet from Middelburg, Zeeland (Netherlands), catalogued as yarn-twister, with incised striped decoration, 950-1050

United Kingdom

- Yorkshire Museum (York Museums Trust, UK)

- Antler lucet (suggested a pendant), 9th-11th century

- Antler lucet or pendant, 5th-9th century

- Antler lucet or pendant, 9th-11th century

- Jorvik Viking Centre, York (UK)

- Bone lucet 11716 from Coppergate, 9th-11th century

- Bone lucet 7408 from Coppergate, 9th-11th century

- Bone lucet 4107 from Coppergate, 9th-11th century

- Antler lucet 9931 from Coppergate, 9th-11th century

- Norfolk Museum Collections – Lynn Museum, Norfolk (UK)

- Bone lucet from Thetford, UK, 10th-11th century

- Norfolk Museum Collections, Norfolk (UK)

- Chertsey Museum (UK)

- Ivory lucet, 18th-19th century

- Ivory lucet with central hole and marks either side where thread has worn the ivory down, 1770-1800

- Museum of English Rural Life, University of Reading (UK)

- Four wooden lucets made by Mr B. Turner, the Technician at MERL, 1976

- Hollytrees Museum, Colchester (UK)

- Two ivory lucets without handle, undated but probably after the 18th century

United States of America

- Cleveland Museum of art

- Lucet in mother-of-pearl and gold, Vienna (Austria), 1765

Finds from the Middle Ages: timeline and map

Here I listed, with images and a map of the finding sites, the finds that have been identified as lucets, not going beyond the end of the Middle Ages.

In several cases, we got just the general indication of the place where an artifact was found, so this map is just a visualisation of the areas where those finds come from.

- Late Antiquity – Early Middle Ages

- Decorated carved bone tool from archaeological ruins in Kirchbichl, Lavant, East Tyrol,

(Austria)

- Decorated carved bone tool from archaeological ruins in Kirchbichl, Lavant, East Tyrol,

- 5th-9th century

- Antler lucet or pendant from York (UK)

- 600-800 AD

- Bronze tool, maybe a lucet, from Övra Vannborga (Sweden)

- Early Middle Ages

- Bone lucet from Grado (Friuli-Venezia-Giulia, Italy)

- 7th-13th century

- Bronze lucet from Hossmo (Sweden)

- 9th-11th century

- Decorated antler lucet or pendant from York (UK)

- Antler lucet or pendant from York (UK)

- Bone lucets from Coppergate, York (UK)

- 950-1050

- Possible lucet from Middelburg, Zeeland (Netherlands)

- 10th-11th century

- Bone lucet from Thetford (UK)

- Three bone “tricotins” from the abbey of Wandignies-Hamage (France)

- 10th-12th century

- Lucets from Sigtuna (Sweden)

- 1020-1050

- Lucet with dotted decoration, 1020-1050

- 1050-1075

- Tempelben or carved lucet from Sigtuna (Sweden)

- 11th century

- Lucet with inscription from Lund (Sweden)

- Tempelben or lucet from Sigtuna (Sweden) (1050-1075 AD)

- 1170-1240

- Bronze lucet from Eketorp (Sweden)

- Bone lucet from Eketorp (Sweden)

- 12th century

- Fragment of an unidentifiable bone handle with broken iron prongs, Landesmuseum Schloss Tirol,

Dorf Tirol (Italy)

- Fragment of an unidentifiable bone handle with broken iron prongs, Landesmuseum Schloss Tirol,

- 13th century

- Two decorated lucets from Örja (Sweden)

- Bone lucet from Oslo (Norway)

- 13h-14th century

- Possible bone lucet from Sonnenburg castle ruins, Natters, North Tyrol (Austria)

- End of 14th – second half of 15th century

- Flute repurposed as a lucet, Linköping, Brevduvan neighborhood (Sweden)

- Middle ages

- Iron tool, maybe lucet, from Borg (Sweden)

- Possible lucet from Patsch, near Innsbruck in North Tyrol (Austria)

Books and articles

- Sara Rossi and Daniel C. Phelps, The Lucet Compendium. A historical exploration and practical guide, The Compleat Anachronist series 202, Society for Creative Anachronism, 2023

- Halldor Magnusson, Evidence for lucets and lucet braiding in Early Medieval Britain and Scandinavia, 2012

- Sylvia Groves, The History of Needlework Tools and Accessories, London, 1966, pp. 93-94 and 102

- Kerstin Pettersson, En gotländsk kvinnas dräkt. Kring ett textilfynd från vikingatiden, in Tor 12, Societas Archaeologica Upsaliensis, Uppsala, 1967-1968, pp. 174 – 200

- A. Rogerson, C. Dallas, M. Archibald, Excavations in Thetford, 1948-59 and 1973-80, Dereham, Norfolk, Norfolk Archaeological Unit, Norfolk Museums Service, 1984, pp.181 (fig. 199), 182 and 199

- Penelope Walton–Rogers, Textile production at 16–22 Coppergate, York, 1997,p. 1790

- Lauwerier R. C. G. M., Heeringen R. M. V., Objects of Bone, Antler and Horn from the Circular Fortress of Oost–Souburg, the Netherlands (AD 900–975), in Medieval Archaeology 39, 1995, pp. 71–90

- MacGregor A., Mainman A.J., Rogers N.S.H., Bone, Antler, Ivory and Horn from Anglo-Scandinavian and Medieval York, London, 1999

- Steenholt Olesen R., Et tinbl:bein fra middelalderens Lund: Et tekstilredskab – men hvilket?, Danske Studier, 2021, pp. 5-24

- Magnus Petersson, Jan-Henrik Fallgren, Maria Rydberg, Övra Vannborg. Arkeologisk undersökning. Övra Vannborga 1:1, Köpings socken, Öland, Kalmar läns museum, Rapport 2009:4

- Haltiner S., Textilhantverk II – nålar och tinbl bein. Makt och människor i kungens Sigtuna. Sigtunautgrävningen 1988-90 (red. S. Tesch), Sigtuna, 1990

- Anders Wikström, Fem Stadsgårdar. Arkeologisk undersökning i kv. Trädgårdsmästaren 9 & 10 i Sigtuna 1988-90, Meddelanden och Rapporter från Sigtuna Museum nr 52, 2011

- Jonas Ros, Duncan Alexander, Ingela Harrysson, Museitomten i Sigtuna. Vikingatida/tidigmedeltida stadsgårdar och kyrkan, Stiftelsen Kulturmiljövård, Rapport 2017:71

- Kirstine Prestmoen Tallerås, Snorgaffel – den glømte reiskapen. Årbok for Nord-Østerdalen, 2008, pp. 119–120

- Beatrix Nutz, Cords, Braids and Bands in Archaeology – Finds from Tyrol, 2022, Strands, pp. 3-9

- Borg K., Näsman U., Wegraeus E., The Excavation of the Eketorp Ring-fort 1964–74, in Eketorp Fortifikation and Settlement on Öland, Sweden, 1976

- Lauwerier R. C. G. M., Heeringen R. M. V., Objects of Bone, Antler and Horn from the Circular Fortress of Oost–Souburg, the Netherlands (AD 900–975), in Medieval Archaeology 39, 1995, pp. 71–90

- Louis Étienne, Les indices d’artisanat dans et autour du monastère de Hamage (Nord), in Bulletin du centre d’études médiévales d’Auxerre | BUCEMA, Hors-série n° 8, 2015

- MacGregor A., Mainman A.J., Rogers N.S.H., Bone, Antler, Ivory and Horn from Anglo-Scandinavian and Medieval York, London, 1999

- Rundkvist Martin, Barshalder 1: A cemetery in Grötlingbo and Fide parishes, Gotland, Sweden, c. AD 1-1100. Excavations and finds 1826-1971, Stockholm, 2003

- Wennerström Ulrika, Palm Veronica and Hansson Martin, Vallgrav vid Hossmo kyrka. Arkeologisk undersökning 2003 samt en fördjupad diskussion om Hossmo som plats under yngre järnålder – tidig medeltid. Hossmo socken, Kalmar län, Småland, Kalmar läns museum Arkeologisk rapport 2008

- Prestmoen Tallerås Kirstine, Snorgaffel – den glømte reiskapen. Årbok for Nord-Østerdalen, 2008, pp. 119–120

Links

- Lucets and lucetting

- Presentation by Beatrix Nutz at the European Textile Forum 2023: “Knitting UFOs: the phantom of the Viking Lucet“

- The Tvinningsben or Lucet

- Viking lucet cord research

- Another reflection on Viking age lucets – Knitted cords, revisited (with links to previous posts)

- About the lucet from Örja, its ecavation and inscription: Med tinbl bein tillverkade man snoddar!

- About the lucets from Norway: Et tinbl bein – NIKU Archaeology Blog

- Lucets in museums

- Lucet glossary in several languages

- Snorgaffel (in Norwegian)

- “The lucet: historically accurate or reenactorism?” on Living Medieval

About updates

This post is a work-in-progress as my research goes on.

Please come back later for future updates.

20 Comments. Leave new

This is a very useful and interesting article! I was trying to figure out if lucets, and/or lucet cords are period for the mid to late 13th century, which (as life would have it) still seems a bit of a questionmark.

But due to my easily derailed ADHD brain I have some general comments unrelated to my original quest.

My spontaneous association with the wide third prong of some of the lucets would be as a way to store them on a belt. This is mainly based on similar shaped parts on the handles of other tools and not in any way specific to lucets, of needle crafts. It would however imply that the lucet was not disposed of after each use, but rather a regularly used (why store it on the belt otherwise) and yet easily lost tool.

And if you consider the idea of holding, or strapping a three pronged lucet in place over the wide prong it could also have something to do with how the tool was used. Although based on the direction of force when making the cord this seems less likely.

But coming back to the question of different sizes and shapes, the third prong and the smaller sized version may be two different solutions to the same problem of storing them on your body. And as so often this may come with slightly different methods of using it. To me the most obvious solution to holding a tiny hollow “pocket/pouch sized” lucet would be to use it like a thimble on top of a finger instead of actually holding it. The only question would be if this leaves enough place for the cord inside, or if it is plausible to run the cord along the outside.

Many ideas and questions which would need further investigation to see how plausible they are, which I obviously don’t have time for.

And despite the fact that I only occasionally dabble in modern lucet cord making I now obviously want a medieval lucet. Just because.

Thank you so much for your opinion, Anna! Yes, the idea of having a small lucet to carry around is a good one I think. I also have two modern lucets, one of which I wanted smaller to fit in a pocket. As for the third prong, another idea I got was it could be used for multicolor or multithread lucet, where you need to keep different yarns separated while working and switching between them. Regarding the carrying on a belt, I am trying to imagine how it could be helpful. Do you have any images of similar tools carried this way?

I am not an archaeologist, but I have a bit of knowledge of many forms of textile working. The temple bone is designed perfectly for what it says it is. Hollow to accomodate a stick, or perhaps, as with modern temples, a set of 2 hinged pieces of wood. The sharp bits would pierce the selvedge of the newly woven section, and the stick would hold the weaving outstretched. The wider, rounded part would act to protect the weaver’sknuckles and/or to hinder catching weft yarn under weaving. Think how difficult it would be to maintain a constant weaving width on the ancient looms where the warp tension is made simply by hanging stones on the yarn ends. A consistant width would be very important when weaving material such as canvas for sails . A temple would give the weaver something to assist in preventing draw-in.

Wow that is mind-opening for me! Do you have any sources I could consult to know more about the use you tell me here? I think it’s exactly the missing link I was looking for. I have to check it with the extant finds. Thank you so much again, your info here is super valuable!

Hi, I’m looking to teach a class on Lucets and their history, may I use your article as a hand out?

Hello. Of course you can! It’s here for the public! If you post about your class on social media, please tag #LRCrafts, I’d love to see it!

Thank you!

You are more than welcome!

My granddad taught me ‘corking’ when I was a very small child, around 5 yrs old, if I remember correctly. He gave me a wooden cotton reel, with 4 nails driven into the top, and a big blunt darning needle, and he taught me what I later learned was also called French Knitting, or spool knitting. I would happily spend hours churning out cord by the meter, and now own several french knitting dollies in various sizes and numbers of prongs, and, most recently, a lucet.

I tell you this, because my first thought upon seeing the size of some of these items was that they could have been made for children. Tiny tools for tiny fingers! I have no evidence to support my idea but that as a small child, I would happily sit and cord my way through a ball of thread or yarn until bored, cramped, or distracted. It would be a simple way for a child to be productive and helpful, and keep them from getting underfoot while the grownups are busy.

Thank you for a wonderful article on the history and mystery of lucets. 😀

Thanks a million to you! Well I think tiny fingers would be handy while using those small tools! Who knows, maybe those tiny bone tools were to teach children, while bigger ones not preserved were for adults. I doubt this, though. Why no evidence of bigger adult artifacts if this is the case? I hope new finds will one day shed some light on the matter.

I would think that there isn’t evidence of bigger adult artifacts because it was considered children’s work and adults had “better” (or harder, more important) things to do. We have to remember children were pressed into “earning their keep” back then, far earlier than we do with our children now. I believe as early as age three they were given age appropriate tasks.

I think Cynthia Juel above has the right idea about these being used as weaving temples. The wide, and longer, tongue or thumb was for preventing the weft (or stray fingers) from getting caught on it. The small hole carved into the back flat part was to insert a pin to hold the bone part in place. I think bone pieces were used because they wouldn’t break as easily as wood and when they did, were easy enough to replace.

Thank you so much for sharing your thoughts! I find the concept of these lucet-like tools being considered children’s tools quite intriguing. It would be fascinating to uncover more evidence regarding textile tasks designed for children.

As for the weaving temple theory, I’m committed to updating the article with additional information. In my upcoming book, “The Lucet Compendium,” set to release in February, I delve into this theory further. The notion that these tools could serve as temples suggests, in my opinion, the need for at least two pieces to create a functional temple, one for each side of the fabric. Since such finds are often unique, the scarcity of multiple similar artifacts from the same context raises questions. It might be attributed to the unpredictability of archaeological discoveries, true, but I find it suspicious.

I would expect finding some of these implements alongside weaving-related objects like loom weights, but the evidence remains limited. Although we have discovered a few Lund-like artifacts in textile production contexts (that I know of, in France and in Sweden), the only instances linked to traces of a loom or weaving practice are from Sigtuna in Sweden. Yet, even there, a direct connection to weaving techniques hasn’t been established.

Moreover, the confirmed preserved temples from the Middle Ages typically feature more than just two or three prongs. I plan to undertake a more in-depth study of Medieval temples to determine whether these tools can indeed be classified as temples or if further exploration is needed. I’ll keep you all posted!

Love learning the history of just about anything!! This was very informative. I learned to use a lucet as recently as 5 years ago. I am proficient in making a cord but nothing decorative like adding beads, etc. One thing that I was taught when I first learned was that in medieval times, ribbon was very expensive so what ladies would do is purchase a short length of ribbon – say just enough for a tiny bow at the neckline and sleeves of a chemise. They used lucet made braid for the draw strings at both neckline and sleeves then attached a tiny bow of decorative ribbon.

Thanks a million, I am glad you liked my research! In the next few months I’ll publish a book about the history of the lucet, then I hope I’ll have time to update this article with other discoveries!

I think the cognate is “thimble”…

Hello! That sounds pretty similar nowadays, but the ancient form was “thȳmel”. The Old English word þȳmel is derived from Old English þūma, the ancestor of the English word thumb. Here I see no direct connection with “tinbl”. I am no linguist, though, so I could be totally wrong! I prefer trusting specialists in this case 🙂 Thanks for pointing out the similarity between the two words, there could come some interesting insight.

The size makes me wonder if lucet, a simple repetitive task, was for young children. While they may not have been throwaway tools even responsible young children loose things and children’s toys/tools are often not as well kept through history as adult things.

Yes, that’s tempting! We don’t have any archaeological context related to children, as I’m aware of, for instance children burials. And textile crafting contexts would not easily give clues about the use of such tools by children, unfortunately. But definitely an hypothesis to keep in mind.

I know my understanding isn’t always great, I’m still learning so much, but what if these tools were used in felting? I know some tools for felting include multiple needles. Could this be a possibility? With the long wide side maybe an edger of some kind?

Well, it could be a possibility. We should check if felting was common practice in the period, the sources we have about it. I don’t know enough about felting to say if the lucet could be a felting tool, but it’s definitely worth checking out, thank you.